Why I Still Teach Of Mice and Men in 2025

I don’t care how many times it’s been taught, Of Mice and Men still lands every single time. There’s something about the final chapter that silences even the rowdiest class. You can hear a pin drop. I’m emotional, some of them get emotional, and suddenly they’re asking, “Wait… why didn’t I see that coming?”

That moment alone makes it worth it.

But beyond the ending, it’s short enough to keep students engaged, and packed with enough talking points to carry weeks of discussion: power, loneliness, race, disability, masculinity, dreams, morality - all wrapped up in about 100 pages.

“It’s Been Done to Death!” And?

Who cares?

There’s a reason Of Mice and Men has been taught for decades. It doesn’t stop being powerful. It doesn’t stop being relevant. It’s a masterclass in symbolism, theme, and foreshadowing — and it always gets students talking.

I usually teach it in Year 9, and for many students, it’s the first text that opens the door to much bigger conversations:

◆ racism

◆ ableism

◆ sexism

◆ loneliness and power

◆ prejudice and social exclusion

Every class I’ve taught it to — one a year, for over ten years — has been fully invested.

And every year, I enforce the same rule without exception:

Do not Google the ending. And if you do, do not spoil it for anyone else.

How I Teach Of Mice and Men (and Keep Students Engaged from Start to Finish)

My goal with this unit is always the same: I want students to think, feel, and argue — respectfully. I don’t just want them to know what happens; I want them to care.

That means blending close reading with creative tasks, structured debate, and quiet reflection.

After each chapter, we use short post-reading creative prompts. These might take the form of:

◆ diary entries

◆ letters

◆ dramatic monologues

◆ short narrative scenes

The key is staying inside the world of the text while shifting perspective. Writing from Crooks’ or Curley’s Wife’s point of view deepens empathy very quickly.

Classroom strategies I use regularly

◆ Silent debates for big moral questions (Was George right? Is Lennie dangerous? Is Curley’s Wife a villain or a victim?)

◆ Roll-the-Dice discussion boards for unpredictable small-group talk

◆ Creative tasks linking symbolism and theme (modern retellings, stage design, costume concepts)

◆ Picture prompts and conscience alley for emotionally charged moments

If you use similar approaches when teaching texts like Macbeth, Animal Farm, or 1984, you’ll find many of the same strategies transfer easily.

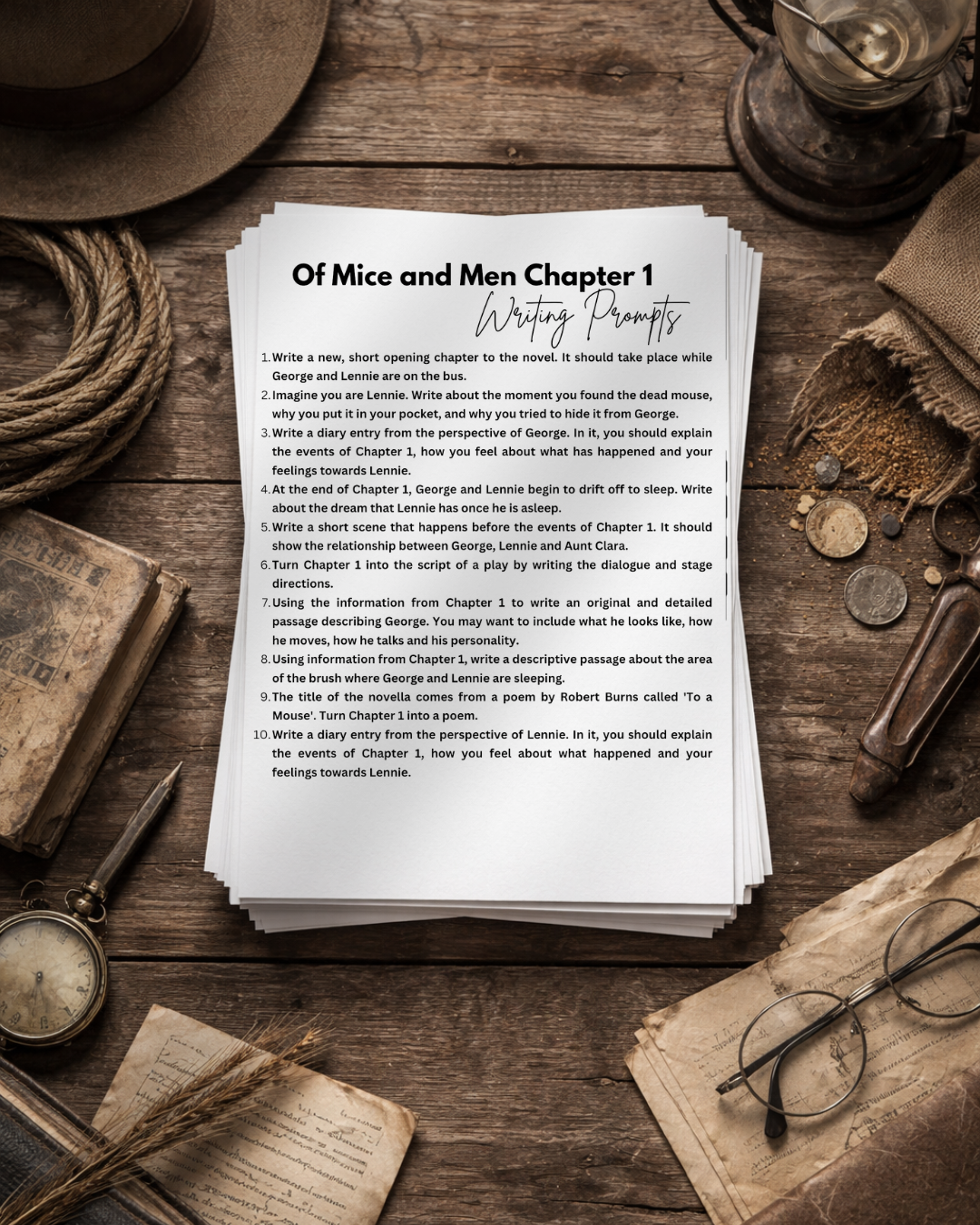

Free Creative Writing Prompts: Chapter 1

If you want a low-effort way to hook students from the very start, you can get 10 creative writing prompts based on Chapter 1 of Of Mice and Men by submitting your email address.

The prompts are designed to:

◆ explore character and setting

◆ encourage empathy and inference

◆ support both creative and analytical thinking

They work particularly well as a pre-reading or post-reading task for the opening chapter. To get them, just drop your email address below

Talking About the Tough Stuff

One of the strengths of Of Mice and Men is how naturally it opens up difficult conversations. The text doesn’t offer easy answers — and that’s exactly why it works.

Instead of giving students an interpretation, I let them debate it out. Silent debates, hot-seating, and thought tunnels allow them to sit with complexity. You can feel the moment when something clicks — when a student finally understands why Crooks shuts down, or why Curley’s Wife lashes out.

It’s not about forcing conclusions. It’s about creating space for disagreement, reflection, and growth.

If this is an area you’re interested in developing further, my post on Teaching Language Through Literature explores how texts like this naturally support difficult but necessary discussions.

What Sticks With Them

Different students connect with different moments — and that’s what makes this unit so powerful.

Some are devastated by Lennie’s death. Others are unsettled by how Curley’s Wife is treated. Candy’s dog nearly always catches them off guard once they notice the parallels.

And George’s final decision? That debate can last days.

Was it kindness or betrayal?

Did he have a choice?

Did Lennie understand?

They feel something — and they remember it.

Final Thoughts

Of Mice and Men isn’t perfect, and that’s exactly why it works. It sparks discomfort, debate, and empathy. Every time I teach it, students notice something new — and so do I.

Whether you’re teaching it for the first time or the tenth, it’s a text that still hits hard. It deserves to be taught with the same complexity it offers.

If you want to save yourself hours of planning, you can grab my full Of Mice and Men bundle on TpT. But however you teach it, just don’t let them Google the ending.