How to Teach Animal Farm: Practical Strategies, Discussion Ideas, and Activities That Actually Work

Animal Farm is one of those texts that students think they’ve “got” after the first read-through, only to realise there’s far more going on once you slow down and look at how Orwell constructs power, language, and responsibility. It’s short enough to fit into a busy term, but rich enough to justify deep reading, creative responses, and genuine critical thinking.

If you teach other political or moral texts like 1984 or Lord of the Flies, you’ll already know how quickly students start mapping authority, control, and group dynamics onto their own world. (I’ve written about how I approach 1984 in the classroom here and Lord of the Flies here if you’re interested in that overlap.)

If you’re teaching Animal Farm soon and want something ready to use, keep reading — there’s a free set of Chapter 1 creative writing prompts further down.

Below, I’m breaking down why it’s worth teaching, how to approach it without drowning students in context, and the kinds of activities that genuinely move students beyond “Napoleon is bad” into something more nuanced and evidence-based.

Why Teach Animal Farm?

◆ It’s accessible without being simplistic.

Students can follow the plot easily — which frees up more lesson time for the good stuff: rhetoric, propaganda, allegory, and the mechanics of power.

◆ It’s a clean way into political literacy.

You don’t need a full lecture on Stalinism before you open the book. The allegory does the heavy lifting once students understand how to read beneath the surface.

◆ It creates natural opportunities for discussion.

Who is responsible? Why do revolutions fail? Why do people comply? These aren’t abstract questions — students recognise versions of these dynamics in schools, friendship groups, and online spaces.

◆ It lends itself to creative and critical response.

From rewriting speeches to analysing the commandments, there’s plenty of room for students to explore the text in ways that feel purposeful rather than performative.

Keep the Context Manageable

A common mistake is front-loading too much historical detail. Students don’t need the entire Russian Revolution in Week 1. What they do need is a working understanding of:

◆ revolution

◆ propaganda

◆ dictatorship

◆ manipulation of language

Once you establish those foundations, the parallels fall into place chapter by chapter. Allow students to make connections as they read rather than handing them a mapping sheet on Day One.

Before Reading: Set Up the Lens

Before jumping into Chapter 1, I like to give students a few anchor points that will guide their reading all the way through:

◆ What makes leadership legitimate?

◆ Why do people accept things they know are unfair?

◆ Can a revolution succeed without becoming corrupt?

◆ How does language shape belief?

These questions give students something to test, challenge, and return to as the novella progresses. They also make the allegory more accessible later.

A short introduction to the idea of allegory (one political cartoon is enough) works far better than a long context lecture. Students remember the visual and transfer that skill across the novel.

During Reading: Focus on Rhetoric, Power, and Language

The most effective lessons during the reading stage are the ones that slow students down and make them actually look at how Orwell constructs the narrative.

Useful focal points include:

◆ Old Major’s speech and the early seeds of rhetoric

◆ How Squealer reframes events

◆ The commandments — and how they shift

◆ The windmill as a symbol of hope, labour, and exploitation

◆ Consolidation of power through fear, language, and ritual

Strategies that tend to work well:

◆ Quote tracking: Students build a running log of propaganda techniques.

◆ Perspective writing: A quick journal entry from a minor animal is often more revealing than a full essay.

◆ Mini-debates: Short, structured talk tasks after Chapters 5–7 deepen understanding without derailing the lesson.

◆ Commandment timeline: Students rewrite the commandments every time they change — the visual impact sticks.

Free Resource: Chapter 1 Creative Writing Prompts

If you’re teaching Chapter 1 soon (or you want something low-prep for a cover lesson), I’ve put together a set of creative writing prompts that let students explore character, perspective, and the early ideological groundwork of the novel.

They work well as quick writes, homework tasks, or extensions.

If you want your free Chapter 1 prompts, enter your email below.

After Reading: Push Them Into the Big Questions

Once students finish the novella, they’re usually ready to tackle the more uncomfortable ideas: complicity, responsibility, and the question of whether the animals themselves play a role in their own oppression.

Useful post-reading activities include:

◆ Silent debates on responsibility and propaganda

◆ Rewrite tasks (e.g., Squealer’s broadcast of an event in Chapter 7)

◆ Analytical writing that focuses on Orwell’s choices rather than plot recall

◆ Revision activities to strengthen retention

◆ Group discussions framed around essential questions rather than character lists

This is where the text starts to click for students — and where the deeper allegorical layer becomes more visible.

Activities That Consistently Work Well With Animal Farm

Creative Writing Tasks

Students respond well to tasks that let them inhabit the text without drifting into fanfiction. These work best when they keep the rhetoric, perspective, and context intact.

Effective formats include:

◆ diary entries from Clover or Benjamin

◆ a short propaganda speech written by Squealer

◆ a news report covering the Rebellion

◆ a micro-story from the perspective of a minor animal

◆ rewriting the Seven Commandments in a modern setting

These tasks build empathy and interpretive depth while drawing attention to Orwell’s rhetorical and structural choices.

Critical Thinking Tasks

To move students beyond “Napoleon is bad,” you need to give them structured space to challenge each other’s thinking and justify positions with evidence.

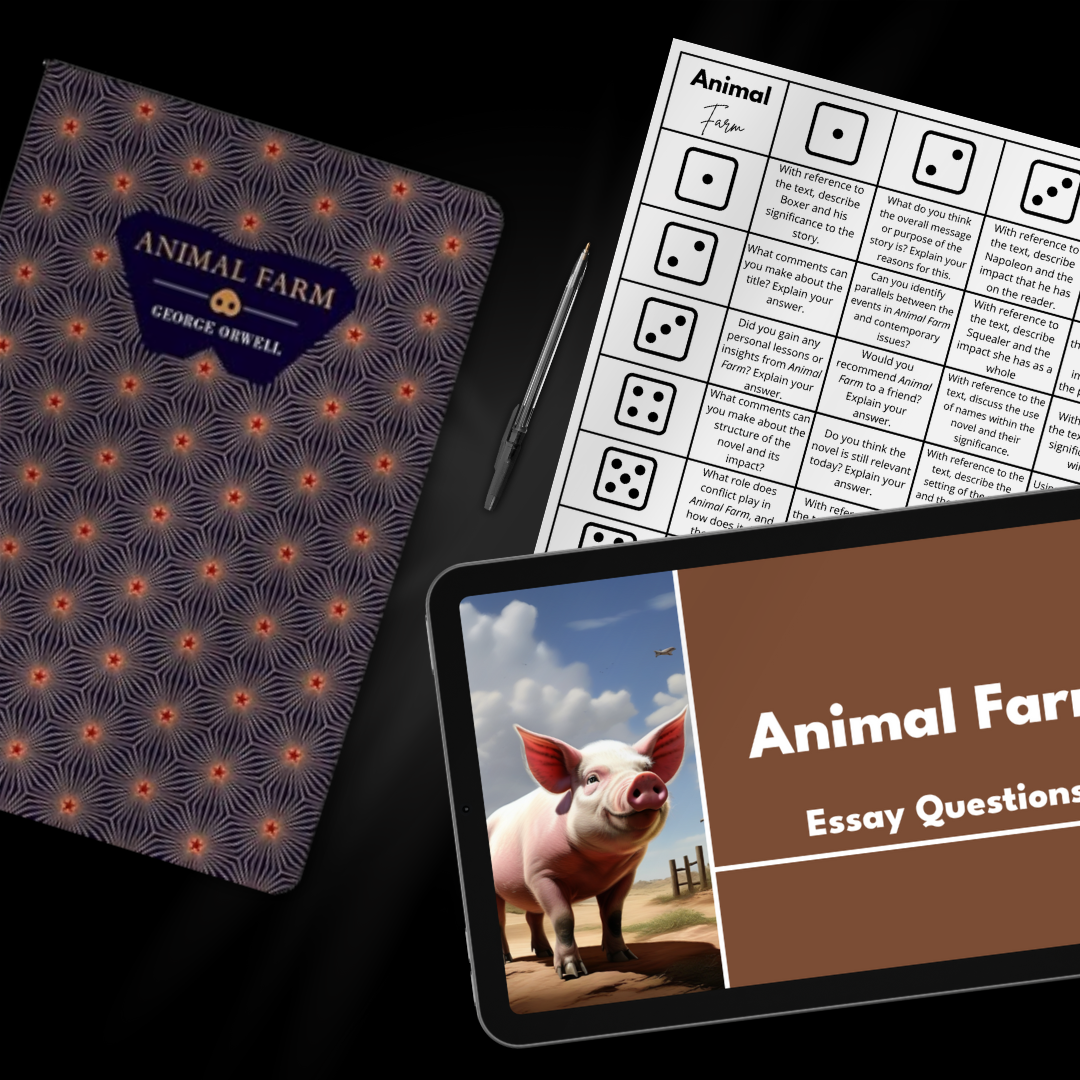

Useful approaches include:

◆ silent debates

◆ roll-the-dice discussion boards

◆ structured seminars

◆ provocations (e.g., “Are the animals partly to blame?”)

These formats tend to produce more nuanced interpretations than whole-class discussions.

Revision and Retrieval

Short, low-stakes revision activities help consolidate knowledge throughout the novella and support confidence heading into assessments. They are also ideal for cover lessons.

Options include:

◆ crosswords

◆ bingo

◆ quizzes

◆ word searches

◆ chapter review questions

These work particularly well for mixed-ability groups where you need differentiation built into the lesson structure.

Animal Farm Growing Bundle (For Teachers Who Want Pre-Made Activities)

If you want a full set of resources you can drop straight into lessons, my Animal Farm Growing Bundle brings together revision tasks, creative writing, discussion activities, and digital materials in one place.

It includes:

◆ creative review tasks

◆ review word search

◆ creative writing prompts (PDF + digital)

◆ roll the dice discussion boards

◆ review bingo

◆ review crossword

◆ digital quizzes

◆ essay questions

◆ chapter review word searches

◆ chapter discussion cards

◆ silent debate questions

◆ picture writing prompts

It’s designed to support flexible teaching — whether you need a quick cover lesson, a full creative sequence, or structured revision approaching an assessment.

You can get the bundle here!

Final Thoughts

The reason Animal Farm works so well in the classroom isn’t because students can memorise who represents whom, but because it invites them to think about how power is gained, preserved, and justified — and what that means for ordinary individuals caught in the middle. With the right mix of discussion, creative response, and retrieval, students quickly move beyond summary into genuine analysis and debate. It’s a text that rewards slow reading, clear questioning, and opportunities for students to test ideas out loud — and the payoff is always worth it.