Teaching The Lottery by Shirley Jackson Without Context (And Why It Works)

Every year, before we read The Lottery by Shirley Jackson, I ask my students one simple question: What do you think this story will be about? The answers are always confident. Someone’s going to win money. A prize. A reward. A celebration. They imagine cheering, relief, maybe a bit of tension — but nothing darker than that. And that assumption is exactly why I don’t teach context first when teaching The Lottery.

Shirley Jackson designed this story to feel ordinary. Familiar. Safe. It opens in sunshine, with children gathering stones and neighbours chatting like it’s a village fête. If students come to the text already armed with historical background, author intent, or warnings about conformity and violence, the story loses its most powerful weapon: the moment of realisation that they went along with it too. When students read The Lottery without context, they experience the shock as readers, not analysts — and that experience changes everything that comes after.

I teach a lot of texts where context is essential from the start. The Lottery isn’t one of them. This is a story that earns its meaning through silence, discomfort, and delayed understanding. And when you trust the text to do its work first, students don’t just understand it — they feel it.

Why Teachers Are Told to Teach Context First

There’s a good reason English teachers are usually encouraged to front-load historical and social context. We’re trained to situate texts within their moment: post-war America, social conformity, the dangers of tradition, the pressure to belong. With most short stories, that framing helps students read more confidently and avoid surface-level misunderstandings.

But The Lottery by Shirley Jackson is a rare case where knowing too much, too soon, actively undermines the reading experience.

When the story was first published in The New Yorker in 1948, readers didn’t receive it as an obvious allegory. They received it as something deeply unsettling — and, crucially, possibly real. The magazine was flooded with letters. People demanded explanations. Some were furious. Others were bewildered. A surprising number simply wanted to know where these lotteries were held, and whether they could go and watch.

Jackson later reflected that the magazine received more mail in response to The Lottery than to any other work of fiction it had published up to that point. Many readers weren’t asking what the story meant — they were asking whether this was something that actually happened. That reaction only makes sense if you imagine encountering the story without context, without warnings, without reassurance that this was “just” a symbolic critique.

Jackson herself acknowledged how disturbing that response was. In later reflections, she described receiving hundreds of letters — many openly hostile — and admitted that she’d never fully considered how violently readers might react to being confronted with something so familiar and so brutal at the same time. Even her own mother wrote to scold her for writing something so gloomy.

And that’s exactly the point.

If students are told in advance that The Lottery is a critique of conformity, or a warning about blind tradition, or a commentary on post-war American society, they approach the story defensively. They read it like a puzzle to be solved rather than an experience to be endured. They’re braced for the ending. They’re protected from the discomfort.

But Shirley Jackson didn’t want her readers protected. She wanted them shocked — not by spectacle, but by recognition. Teaching too much context too early doesn’t deepen understanding here; it softens the blow. And The Lottery only works when the blow lands.

Why The Lottery is Different

Most short stories reward preparation. The Lottery by Shirley Jackson punishes it.

This is a text engineered around misdirection. From its opening lines, the story establishes a world that feels familiar, even comforting: a warm June morning, neighbours gathering, children at play. The language is deliberately plain. The setting is deliberately ordinary. Nothing signals danger. And that’s not accidental — it’s the mechanism.

Jackson isn’t building suspense in the conventional sense. She’s building compliance. Readers accept the ritual because everyone else does. They accept the rules because no one questions them. Even the children gathering stones doesn’t immediately register as a threat, because the story has trained us to read the scene as harmless. When students read The Lottery without context, they do exactly what the villagers do: they participate.

That’s why foreknowledge changes the experience so fundamentally. If students know in advance that the story is a critique of blind tradition or social conformity, they read with distance. They’re alert. Suspicious. They scan for symbols instead of absorbing the atmosphere. The quiet horror of the story isn’t that the violence happens — it’s that it happens because everyone agrees to it. And that realisation only lands if the reader isn’t braced for it.

In many classrooms, the ending of The Lottery is treated like a twist. It isn’t. There’s no sudden shift in tone or style. The same calm, measured language carries us all the way through. What changes is the reader’s understanding of what they’ve already accepted. The shock comes from recognising how easily normality slid into brutality — and how little resistance it met along the way.

This is why teaching The Lottery without context works. The story isn’t asking students to decode meaning from a safe distance. It’s asking them to feel what it’s like to belong to a system that harms, and to realise — too late — that they never questioned it. When students experience that first, everything that follows becomes richer, sharper, and far more difficult to dismiss.

What Happens When Students Read The Lottery Cold?

When students encounter The Lottery without context, the lesson follows a pattern that’s surprisingly consistent from class to class.

The Assumption of Safety

The opening of The Lottery rarely sets off alarm bells. Students recognise the setting immediately: a small community, children playing, neighbours gathering in the sunshine. It feels familiar and unthreatening, and that familiarity does a lot of work. There’s often quiet confidence in the room at this stage — the sense that this is going to be a story about community, tradition, or perhaps even celebration.

Because nothing signals danger, students relax into the narrative. They read quickly. They don’t overthink the details. The story feels manageable.

Going Along With It

As the ritual begins to take shape, students notice the oddness without fully resisting it. The language remains calm. The tone remains steady. Children collecting stones registers as strange, but not yet sinister. The villagers’ unquestioning participation feels unsettling in retrospect, but in the moment it passes without comment.

This is where Jackson’s control is most evident. The story never demands outrage. It simply presents the ritual as normal, and students — like the villagers — accept that normality because everyone else does. Reading The Lottery without context allows that quiet compliance to happen naturally.

The Moment the Room Changes

The shift doesn’t come with gasps or dramatic reactions. It comes with silence.

When the truth of the lottery becomes clear, the room stills. Students stop reading ahead. Someone usually looks up, as if checking they’ve understood correctly. The horror isn’t loud — it’s internal. They realise what the stones are for. They realise who the ritual targets. And, crucially, they realise how long they went along with it.

That recognition is uncomfortable, and it should be.

Looking Back and Re-reading

Almost without fail, students want to go back. They re-read the opening with new eyes. Innocent details become loaded. Casual phrases feel cruel. The story hasn’t changed — but their understanding of it has, completely.

This is the point where the discussion deepens. Students don’t need to be told that the story is about conformity or tradition or collective violence. They’ve experienced it. And once that experience is in place, everything else — analysis, context, interpretation — has somewhere meaningful to land.

Why I Delay Context (And What I Do Instead)

Delaying context doesn’t mean removing it altogether. It means changing the order so that understanding grows out of experience rather than being imposed in advance. With The Lottery, that order matters.

I Let Students Predict First

Before we read, I ask students what they think a story called The Lottery will involve. The guesses are almost always optimistic: money, luck, celebration, maybe a winner and a loser. Those assumptions tell me everything I need to know about the expectations they bring to the text — and they become important later.

At this stage, I don’t correct them. I don’t hint. I let those ideas sit.

We Read Without Warnings

We read the story straight through, without historical framing, author background, or interpretive cues. I don’t soften the language or pre-empt the ending. Students meet the village exactly as Jackson presents it: ordinary, communal, unremarkable.

This matters. The absence of warning allows the story to do what it was designed to do — to draw readers in quietly, without resistance.

We Sit With the Discomfort

When the truth of the lottery becomes clear, I don’t rush to explain it. We pause. We talk about reactions before meanings. Shock, anger, confusion — all of that comes first.

Only once students have processed the experience do we start to articulate why it feels so disturbing. At that point, they’re not searching for the “right answer”. They’re trying to make sense of something that’s unsettled them.

Context Comes After Experience

This is when context finally earns its place. When students learn about the response to the story’s publication — the letters, the outrage, the belief that it might be real — it doesn’t feel like trivia. It feels inevitable.

By the time we introduce historical context, author intention, and critical interpretations, students already understand the story’s power. Context deepens that understanding rather than replacing it. And because they’ve experienced the story first, they’re far more willing to engage seriously with what comes next.

The Resources I Use When Teaching The Lottery

Once students have experienced The Lottery by Shirley Jackson without context and we’ve unpacked those first reactions together, that’s when I start to bring in more structured activities. At this point, students are ready for deeper thinking — not because they’ve been told what the story means, but because they want to explore it.

The resources I use are designed to build on that initial shock rather than dilute it. They focus on interpretation, discussion, and creative response, giving students multiple ways to process the story beyond a single analytical paragraph.

In my classroom, I use my The Lottery Teaching Bundle on TpT, which brings together a wide range of activities to support different learning styles and classroom needs. It works particularly well after a first, unframed reading, when students are full of questions and ideas.

The bundle currently includes:

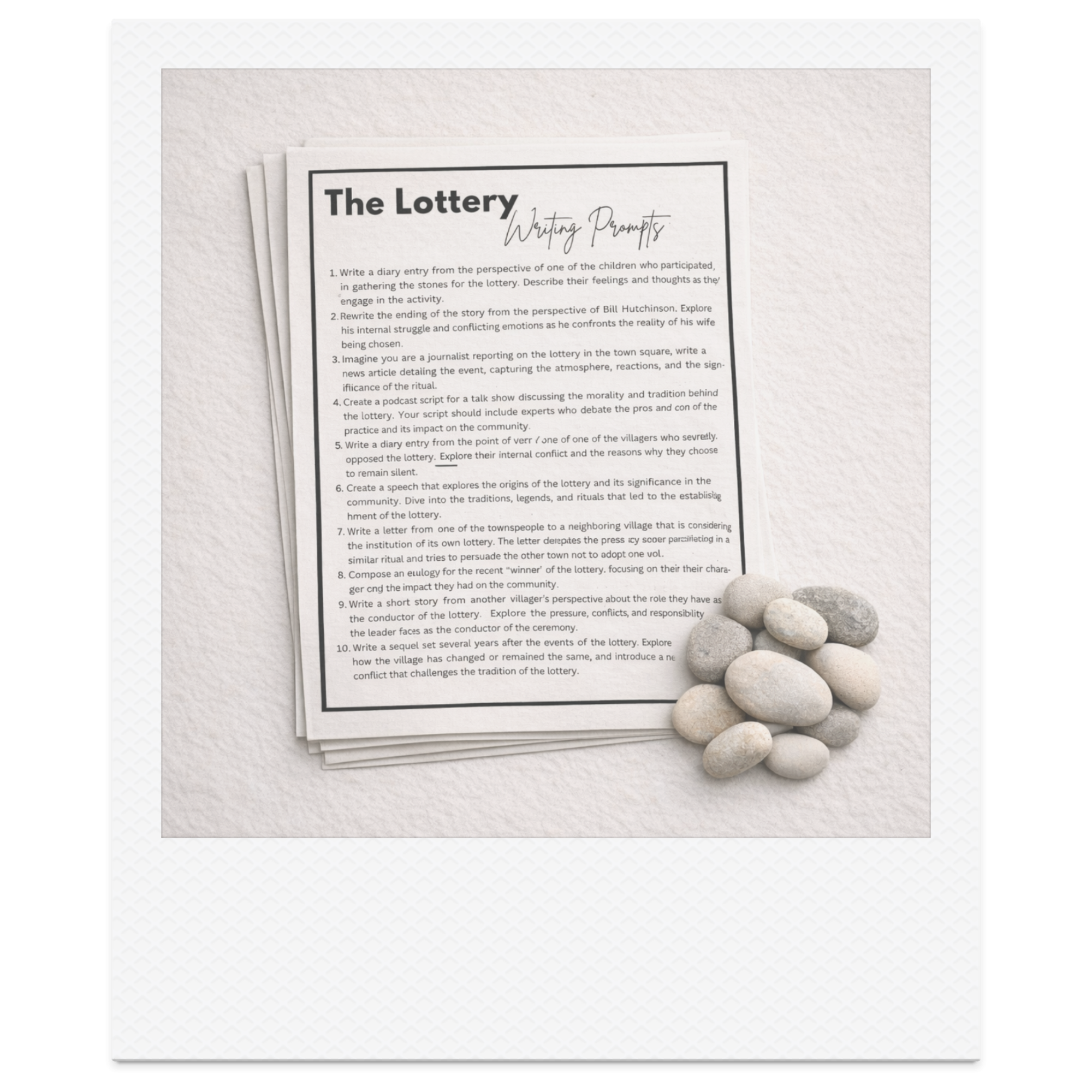

◆ Post-Reading Creative Writing Prompts (PDF and digital versions) that encourage students to explore themes, character, setting, and moral responsibility through imaginative and reflective writing

◆ Creative Response Tasks that allow students to engage with the story visually, narratively, and conceptually

◆ Roll the Dice Discussion Boards with 36 prompts, ideal for small-group or paired discussion once students are ready to articulate their thinking

◆ Picture Prompts for Descriptive and Narrative Writing, which help students revisit the village and its rituals from new perspectives

◆ Silent Debate, where students respond to provocative statements about conformity, tradition, and collective violence in writing

◆ Essay Questions designed to push beyond surface interpretations

◆ Interactive Review Activities including a word search, crossword, bingo game, and a digital multiple-choice quiz for retrieval and consolidation

What I like about using these resources after the initial reading is that they don’t tell students what to think. Instead, they give structure to conversations that are already happening — helping students clarify ideas, challenge each other, and return to the text with sharper focus.

Used this way, resources don’t replace the reading experience. They deepen it.

Go Deeper: Ritual, Tradition, and Collective Violence

Once students grasp the unsettling power of The Lottery by Shirley Jackson, the story opens naturally into wider conversations about ritual, inherited violence, and communal responsibility. This is where the text stops being a one-off shock and becomes part of a broader literary pattern.

To deepen students’ understanding, it can be useful to explore how The Lottery sits alongside other stories that examine what happens when tradition goes unquestioned:

◆ Pair The Lottery with other short stories that expose the danger of conformity and social pressure, such as The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (Le Guin) or The Possibility of Evil (Jackson), asking students to compare how communities justify harm

◆ Explore ritual as a narrative device, focusing on how ordinary language and repeated actions normalise violence

◆ Return to earlier moments in the story after discussion, encouraging students to track how meaning shifts once the ending is known

◆ Frame discussions around responsibility, not just symbolism — who is accountable when “everyone” participates?

At this stage, students are often ready to move beyond analysis and into imaginative response. This is where I sometimes introduce The Kindling Collection, an immersive creative writing experience inspired by folklore, ritual, and eerie village traditions.

Set in the remote village of Ashwick during the Longlight Festival, The Kindling Collection invites writers to piece together a fragmented narrative through letters, warnings, lost journal pages, and unsettling ephemera. Like The Lottery, it centres on a community bound by tradition — and the quiet menace hidden beneath celebration.

Used alongside The Lottery, it works particularly well as a creative extension:

◆ Students can create their own ritual-based narratives, drawing on the idea of festivals that demand participation

◆ Writers can explore unreliable traditions, contradictory accounts, and silences within a community

◆ Classes can discuss how folklore and ritual evolve — and why people continue them even when harm is evident

Because there is no single storyline or “correct” interpretation, the collection mirrors the moral ambiguity at the heart of The Lottery, encouraging students to sit with uncertainty rather than resolve it too quickly.

Final Thoughts

The Lottery endures because it refuses to reassure. It doesn’t soften its message or offer easy villains. Instead, it asks readers to confront how ordinary people maintain violent systems simply by going along with them.

Teaching The Lottery without context allows students to experience that discomfort firsthand. Rather than being told what to think, they discover — often to their own surprise — how easily familiarity becomes complicity. Context, when introduced later, sharpens that realisation instead of dulling it.

Approached this way, The Lottery becomes more than a short story for assessment. It becomes a lesson in moral responsibility, reader participation, and the quiet power of tradition. Students don’t just analyse the text; they recognise themselves within it.

And that is why it still matters.